Catastrophic storms drenched California. A year’s worth of rain fell on Los Angeles in a day. At the same time, wildfires raged in Chile. At least 131 people were killed, and thousands were left homeless.

The cause of each of these emergencies? A combination of an El Niño weather pattern exacerbated by human-caused climate change, what The New York Times described as “a dangerous cocktail.”

Unfortunately, these emergencies are not isolated events. In fact, they arrived on the heels of heat waves that swept the US, Australia, Europe, and Asia. A super typhoon that battered the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, and Guam. Floods, droughts, hurricanes, and a historic number of billion-dollar disasters that landed in 2023.

Leaders of businesses and governments often speak about these events as being unprecedented, unseasonable, and untenable. The reality is these types of events are becoming more common than ever before. What leaders need most is a way to understand this increasing uncertainty.

The first step in solving a complex problem is to see that problem with clarity, to understand it from different perspectives. This approach has never been needed more than it is now with a changing climate, perhaps the most formidable challenge facing the world today. It affects business operations, government national security, and most importantly, people’s lives in communities around the world.

For thousands of years, humans have understood the world through maps. Maps are a language. Maps tell us about our planet’s past and present. They help us understand and they allow us to make valid predictions. Now, maps are critical for turning climate uncertainty into climate action.

Intense Climate Events Mean We Are Going to Need Better Maps

As an exercise, try to visualize the connection between the California and Chile disasters. Your inclination probably will be to imagine a map, much like an explorer of old navigating between two distant locations.

You’ll likely encounter two challenges.

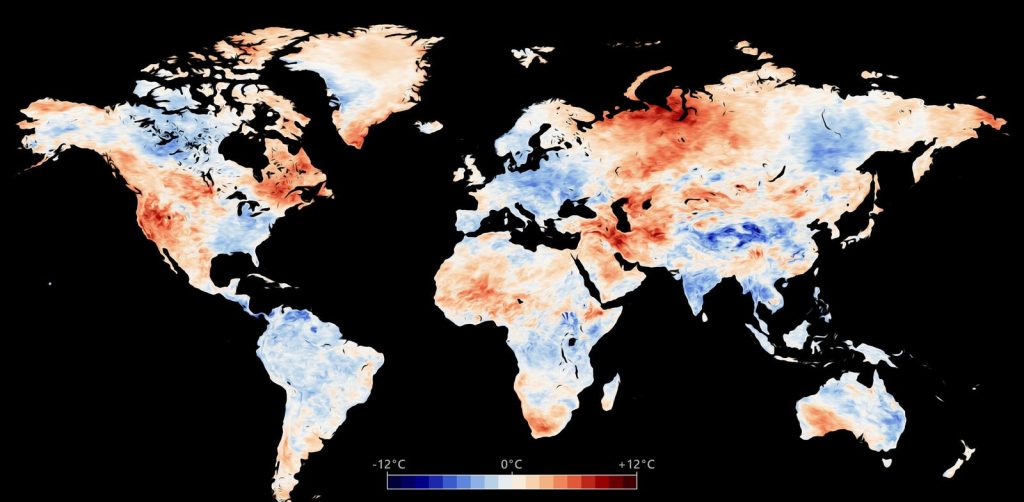

First, the geographic scope makes the connection difficult to comprehend. Five thousand miles separate California and Chile. It is like trying to imagine the same atmospheric conditions simultaneously causing extreme—but disparate—weather conditions in New York and Hawaii. And these locations may not be familiar to you at all – you will have questions about where they are or what is nearby. You would want to see important details like human settlements, critical infrastructure, coastal shorelines, and historic weather patterns.

Second—and much more puzzling—you would need to visualize the complicated interaction between El Niño and climate change, not just the location of the emergency itself. You would want to know how and where the intermingling of these two forces accounts for floods in one location and fires in another and perhaps where the next emergency might arise.

What you’re really doing is trying to imagine layers of information on a map, each combining to aid in your understanding of the location and the emerging situation. And remember, it’s a big map. The amount of information is staggering.

But this is the world we now live in. Understanding extreme weather events related to climate change means visualizing connections across space and time, with a dizzying number of potential interactions.

Geography Matters More Than Ever

One crucial factor in understanding all this information and all these interactions is geography. These weather-related events all play out in specific places. And how they affect people and communities in these places is complex. A weather event in one location may have vastly different impacts and outcomes had it occurred in another location—we see this every day on the news.

For that reason, responding to climate-related impacts and increasing risks demands a geographic approach. It demands new maps. Digital, interactive maps that organize layers upon layers of critical data to show connections and patterns and hotspots—both locally and across very large areas.

These new maps are made with geographic information system technology, or GIS. This next-level mapping can bring in early wildfire detection data from sensors. It can simulate flood scenarios. It can use imagery from satellites and drones to monitor hazard conditions in real time. Its AI machine learning can test virtual models of bridges or buildings or entire cities to find areas of vulnerability and opportunities for risk reduction efforts, mitigation, and adaptation.

GIS is not the sole solution to the climate crisis. But it is arguably the most powerful tool available to understand it, measure its effects, and—most importantly in the short-term—manage our preparation for and recovery from the emergencies it causes. In other words, GIS is the tool we need to take action.

As natural hazards increase in both number and severity, the need to make quick and sound decisions becomes more urgent. First responders need to be able to strategize in the moment, as well as understand how their actions might change over the next few hours or days.

Shared GIS maps, accessible via mobile devices to rescuers in the thick of the emergency, tie teams together. Maps and dashboards allow responders to integrate meaningful data such as regional weather forecasts, demographic information, and transportation networks to understand which areas are still at risk.

Answering Tough Questions About Climate Emergencies

Emergencies like floods and fires hit regularly now, and are not all considered a disaster. Something often lost in the discussion over how to deal with the “natural disasters” exacerbated by climate change is that they aren’t really “natural.” In fact, our choices and actions, or a lack thereof, are often what tip an emergency into a disaster.

In these moments, several questions ring loud. How could we have avoided this disaster? What was done to prepare the community for this level of event? What are we doing to help those who have been hurt or displaced? How do we plan better in an effort to avoid a disaster next time?

These questions all require us to make hard choices about what we’re willing to do and where to take action. We know that communities, neighborhoods, and people do not all need the same level of help to become more resilient. The inequities that exist before an emergency are only exacerbated in the moment. This means building climate resilience requires that we work to understand the vulnerabilities, needs, and risks more holistically, and target our efforts accordingly.

GIS maps help make these critical decisions as data-driven as possible. They allow officials to break down the urgent and complex issue of climate change, working across countries and continents, states and territories, and locally within communities and neighborhoods. This is how we turn the global climate change problem into locally meaningful action and build resilience for the future.

Read the full article here